By David Frawley (Pandit Vamadeva Shastri)

The proposed Aryan Invasion or Migration into India that most history books present as a fact so far has not yet yielded any solid evidence to support it. There is no archaeological, genetic, or literary evidence that shows it to be the case. On the contrary, existing evidence is of a continuous development of civilization in India since the end of the last Ice Age.

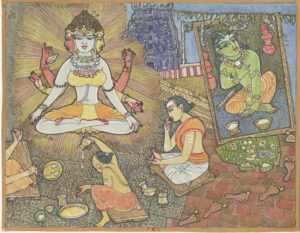

The proposed destroyed cities of the Indus Valley have proved to be a myth, with no real evidence of any destruction by invaders. There is no evidence of Aryan ethnic types, Aryan horses, Aryan cows or anything Aryan leaving any trail into India in ancient times. There is no Aryan culture in ancient India apart from the indigenous culture of the region that exhibits fire altars, Brahma bulls, figures in meditation and Yoga postures, swastikas, chakras, pippal leafs and other symbols quite in harmony with later Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism, traditions that called themselves Aryan.

The only so-called evidence left that claims any real evidence of an Aryan intrusion is linguistic speculation: that affinities between Indian and European languages require that the Vedic culture came from Central Asia in late ancient times. In this article, we will examine the role of linguistics and why we cannot use it as a primary means for determining culture or history. This means that so-called linguistic proof of the Aryans is as questionable as the others. In fact, the term Aryan, which in Sanskrit means noble or pure, has no racial connotation until colonial European scholars proposed it a few centuries ago.

Culture and Language

In order to understand the role of linguistics in determining ancient history, we first need to understand the place of language in human culture. In this regard, spoken language is one of several important factors of culture but not the only one or necessarily the most important.

Civilization and culture are based mainly upon the primary structures of religious, political and social organization which make up the customs, practices and laws of a people. Behind these are the practical necessities of the geography and climate of the region in which the people live. These factors develop in a particular historical context and in an interaction with other such cultures.

Culture is, therefore, a complex phenomenon consisting of varied social and natural factors. To understand, it we must take a broad view of its various aspects. We must avoid the temptation to reduce a culture to a single factor like language, religion, ethnicity or geography and use that as the last word or sole determinative factor. To identify language, culture and even ethnicity, which the Aryan theory has tended to do, is a wrong identification, a confusion of factors that are seldom homogenous in existing cultures.

Each culture certainly has a particular language that we indeed must recognize in order to understand it. This ‘cultural language’, however is, first of all, not a particular spoken tongue, but the terminology of the culture according to its prime values, beliefs, attitudes, and customs. These key words, phrases, ideas or beliefs could be called the ‘prime mantras’ of the culture. To understand a culture, we must understand this language, which means understanding the particular culture’s way of thinking and looking at the world, not just its grammar or etymology as linguistics tend to focus on.

Some cultures – generally with strong national boundaries and limited historical horizons – are dominated by a single outer language, like the German language for German culture. This ‘national language’ may reflect the culture as a whole, being the main spoken language used by the people living in it and and also reflecting its prime values. But this is the exception.

Certain broader ‘cultural languages’ have arisen over time relative to complex civilizations or empires like Greek for Hellenistic culture, Latin for the Roman empire, Sanskrit for classical India or Mandarin for China. These cultural languages have not been the spoken language that all or even most of the people residing in these cultures used in their daily lives. They were a lingua franca or language of general communication for economic, business, intellectual or religious purposes.

Other cultures or cultural zones may be dominated by a particular language family like Indo-European languages for European culture. Here the cultural connection is more general and uncertain. A language family can reflect a number of cultures and various historical changes. It is a far more tenuous entity than a particular language or dialect. We cannot give too much emphasis on it as a determinative factor of culture and it more easily crosses over many cultures and geographical regions.

Much more important than the outer form of the language is the inner culture that the formal language serves as a vehicle for. In other words, the prime ideas and values of a culture are more important than the outer language forms it adopts.

In fact, a non-Indo-European language like Hungarian can easily be used as a vehicle for European culture; just as a non-Indo-European language like Tamil can be used as a vehicle for Indian culture. The nature of the culture is more important than the structure of the language used to transmit it. And some degree of linguistic diversity exists in all cultures, whether it is non-Indo-European languages like Basque or Finnish in Europe, or those in India like Tamil.

Linguistic Reductionism

To try to reduce culture to outer linguistic and grammatical forms is a mistake of thought, a kind of one-sided reductionism. By isolating outer factors as the most important, the inner essence and development of the culture can be obscured or lost.

This issue is particularly important for the Indo-European problem, where there has been an effort to use linguistics – which is focusing on the outer language forms as the primary factor for determining culture – in trying to understand the history, culture and even ethnicity of those speaking Indo-European languages. There has been an attempt to reconstruct a Proto-Indo-European culture as part of a Proto-Indo-European language, for time periods centuries or millennia before we have any written record and try to derive the culture of all later Indo-European speaking groups from it, like a tree from a seed..

This reduction of culture to a particular outer language form is untenable to a deeper view. We cannot define culture by a spoken language, though we can use culture to understand a spoken language.

This means that there is no Indo-European culture that can be defined on linguistic grounds, whether relating to PIE (Proto-Indo-European) or later. There are only Indo-European languages and even this affiliation is rather loose. Indo-European languages can share many factors with non-Indo-European languages as well as have their own differences that can be more major than their similarities.

Indo-European languages can reflect any number of cultures through various different places and historical periods like the Hindu, Persian, Greek, Roman or French. We cannot reduce all these cultures to some single original monolithic linguistic cultural entity called ‘Indo-European’. It would be like defining the development of modern civilization according to sound shifts in the English language, as if science and technology were by products of English language variations!

Yet this is what linguists do when they try to use proposed language shifts in Indo-European tongues to identify some original Indo-European language, culture and ethnicity from which they all arose.

Our understanding of ancient India has in particular suffered greatly from this ‘linguistic reductionism’. There has been an effort to take ancient Indian teachings like the Vedas that are composed in an Indo-European language, remove them from India and from the key ideas and values of Indic civilization, and try to explain them according to language developments of European languages and the ideas of comparative European mythology. This negates Vedic spirituality and culture almost altogether.

There is an Indic civilization and many Indic cultures but these are not limited only to those who speak certain Indo-European languages. There is a European civilization and many European cultures but these are also not limited to Indo-European language speakers.

European civilization can be briefly described as a combination of Judaeo-Christian religious views, Greco-Roman social and political views, and folk practices of the peoples in a certain geographic region and time period, leading to internal developments of art, science and other social changes. Most European groups speak Indo-European languages, but the primary religious ethos comes from a non-Indo-European language speaking culture altogether! We cannot speak of European civilization primarily as a certain Indo-European linguistic entity, nor understand its historical development according to morphological changes in these tongues.

Similarly, we can speak of Indian civilization as a combination of Indic dharma traditions like the Hindu and Buddhist, their corresponding political and social orders, the folk practices of the peoples as developed in the Indian subcontinent, as modified by Islamic, Christian and Western influences in recent centuries and other internal developments. We cannot speak of Indic civilization as primarily a linguistic entity, whether Aryan or Dravidian or both, whether indigenous or coming from the outside. Indic civilization has its own value and identity through its different forms and phases, just as European civilization does.

Most importantly, the prime concepts of Indian civilization are present in the ancient Vedic texts including ideas like dharma and karma, practices like mantra and meditation, an honoring of great rishis and sages, a pluralistic view of reality, and a recognition of the Divine presence permeating the world of nature. They are also present in ancient Tamil and other Indian languages, both of the Indo-European and Dravidian language families, as also in Nepalese.

Yet when linguists look at ancient India, they try to define its people and culture by outer language considerations, particularly Aryan versus unaryan, as if the people of those ancient times neatly defined themselves according to the modern idea of discrete language groups, treating those who spoke languages from other language families as inherently alien to them. The ancient world had a great deal of linguistic diversity and even those speaking languages belonging loosely to the same language family were certainly not aware of it!

The Vedic people of ancient India did not identify themselves as a linguistic entity but as a cultural and religious entity (in which language, of course, had some part, with Sanskrit as their main sacred tongue). Their divisions of Aryan and unaryan were not simple linguistic divisions but cultural divisions of good and bad, friend and foe. Even in the Rig Veda, the oldest Vedic text, Vedic tribes of all the five groups of Turvashas, Yadus, Anus, Druhyus and Purus – which included those who spoke the same or kindred tongues – can be found at times lumped among the Dasyus or enemies of the Aryans.

The search for an original PIE culture is inherently questionable. Language and culture cannot simply be equated. Even if some original PIE existed to some degree as a language, it may not have had any particular culture associated with it apart from the other cultures around it which spoke different languages. There is no way to identify PIE from non-PIE speakers from a cultural standpoint, whether in terms of horses, birch, salmon or anything else. That PIE might have had such words doesn’t mean that non-PIE groups did not have them.

Conclusion

Civilization and culture combine many factors. When we isolate a peripheral factor like language family and try to make it stand on its own as the prime determinative factor, we easily run into confusion. When we try to reconstruct languages for prehistoric periods, where we have no records to verify our speculations, and try to identify them with a particular culture or locale, we are on even yet shakier grounds.

To really understand Indian civilization requires first that we understand the values, perceptions, and aspirations behind it, not just the morphology of Indo-European languages. That is the real study of Indian civilization through which its culture, history and languages can be determined in their proper place. Those who use linguistics to study ancient India usually ignore this altogether. They have missed Indian civilization and its spiritual greatness and are trapped in their own linguistic swamps, trying to define single words and missing the great ocean of spiritual meaning that is our true heritage from the ancient world.

Does this mean that linguistics has no place in the examination of ancient history? No, but that its role is secondary, not primary. It cannot substitute for more solid forms of evidence. We must learn to understand what the ancients said and meant, not just classify whatever grammar fragments we have found as their real message! Otherwise our ignorance of our real history remains. In this regard, the spiritual message of the Vedas is as unrecognized today after some centuries of linguistics, as it was before that discipline arose.