From Keynote talk by Dr David Frawley at for Sanchi University of Buddhist and Indic Studies on March 1, 2014, 2nd International Conference on Dharma-Dhamma.

Yoga Dharma

Yoga is one of the primary themes and most important practices in all Indic or Bharatiya Traditions along with that of Dharma. Dharma refers to the natural, ethical and spiritual laws of the universe, which reflect the underlying unity, harmony and interdependence of all existence.

Yoga refers to the unity and integration of energies, particularly the unification of the individual with the universe as a whole at the level of consciousness, which is perhaps the ultimate pursuit of Dharma. Yoga relates to internal practices to bring peace and harmony to body and mind in order to access a higher awareness that reflects an understanding of dharma.

Dharma usually implies following some type of Yoga practice or sadhana. We could say that “Yoga is the practice of Dharma,” and “Dharma is the principle or worldview behind Yoga.” We cannot separate the study of Yoga traditions from that of Dharma traditions. These are two related approaches of examining the same teachings.

Yoga is often called “Yoga Dharma” in Hindu thought. Yoga Dharma relates to Moksha Dharma, the highest of the dharmas, pursharthas or goals of life, the freedom of the spirit, and liberation from all ignorance, bondage and sorrow, what is also called Kaivalya and Nirvana.

Types of Yoga

There are many definitions of Yoga in traditional texts. Most of these revolve around Yoga as control of the mind, the practice of meditation, concentration, equanimity or samadhi, or related means like asana and pranayama for preparing the body and mind for meditation. In this regard, we cannot separate the study of Yoga from the study of meditation.

Yoga in the broader sense of the term refers to a whole range of spiritual practices including asana, pranayama, ritual, mantra and meditation, performed in a systematic manner as a comprehensive approach to inner development, a science of Self-realization.

Yoga is divided into different types of Yoga as Jnana Yoga (Yoga of Knowledge), Bhakti Yoga (Yoga of Devotion), Karma Yoga (Yoga of Action, including ritual and service), Mantra Yoga, Laya Yoga, Kundalini Yoga, and several others, which overlap in various ways. Each of these types of Yoga has its authoritative texts and characteristic practices, though with a good deal in common with other Yoga approaches.

Yoga as a term arises first in the Rigveda (V.81.1) relative to controlling the mind:

Yunjante manasa uta yunjante dhiyo

Vipra viprasya brihato vipascitah

Seers of the vast illumined seer

They yogically control their minds and their intelligence

This verse is also quoted by the Upanishads (Svetshvatara II) relative to the practice of Yoga.

The Rigveda presents what can likely be called the oldest form of Yoga as Mantra Yoga, in verses like the famous Gayatri mantra to the Sun, the most commonly used prayer of the Hindus, performed at sunrise, noon and sunset. Yet one can find the approaches of knowledge, devotion, ritual and pranic practices in the Rigveda as well, or the seeds of most of later Yoga.

Classical Yoga like the Vedas, and several Buddhist traditions, is rooted in Om as pranava or primordial sound and uses various seed mantras and name mantras from which Mantra Yoga practices arise. These mantras are characterized by the use of the term nama, meaning reverence, as in Om namah Shivaya. Om Buddhaya Namah, reverence to Shiva, reverence to Buddha.

Yoga as a term becomes more prominent in the Bhagavad Gita and Puranas. Yet related terms for various aspects of Yoga practice like tapas, dhyana, mantra, svadhyaya, and many others are common in earlier Vedic texts. Even the Vedic idea of Yajna, meaning sacrifice or sacred action, relates to Yoga as an inner type of sacrifice, offering prana, speech and mind to the Divine light within. We cannot look at Yoga merely as a word but according to its related practices and many aspects. In this regard, we must remember the wealth of synonyms that exists in Sanskrit. No single term can be made the final determinant of any dharmic approach, which always transcends mere semantics.

Yoga Darshana

One of the six schools of classical Vedic philosophy (Shad darshanas) is called Yoga or “Yoga Darshana,” which is generally allied with Samkhya, another of the six schools. Some scholars look at Yoga mainly in terms of Yoga Darshana. Yet the concept, idea and practice of Yoga in various forms exists to some degree in all six Vedic darshanas. For example, Vedanta or Uttara Mimamsa we could say deals with Yoga as Jnana and Bhakti, knowledge and devotion, teaching Self-inquiry and surrender to God. Purva Mimamsa, we could say, deals with Karma or ritual and thereby Karma Yoga.

Yoga Darshana’s prime text is Patanjali Yoga Sutras, which like all the Darshana texts is part of Hindu Smriti literature and rests upon the Vedas as its Shruti or the revealed text. Yoga Sutras remain one of the most important Sanskrit texts.

Yet the founder of the Yoga Darshana system is not Patanjali, but an earlier figure of Hiranyagarbha, for whom no specific text remains, but many references exist, particularly in the Mahabharata, whose Yoga teachings emphasize Hiranyagarbha and do not mention Patanjali who likely came later.

Yoga Darshana is often called Ashtanga Yoga for its teaching of an Eight-limbed Yoga (though this is not its only approach). It is also called Raja Yoga, the Royal Yoga owing to its working directly on the mind. There are other schools of Raja Yoga besides that of the Yoga Sutras as well. Hatha Yoga is often contrasted to Raja Yoga as working more with the body and the prana, as to Raja with mind and will power.

Other Yoga Schools

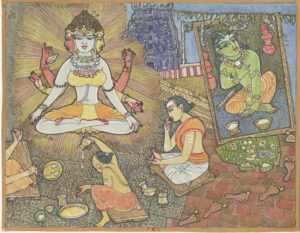

Shaivism has many Yoga traditions with the Nath and Siddha Yogis. Most of the Himalayan Hindu Yogis are Shaivites and Shiva himself is the great lord of Yoga, Yogeshvara. These Shaivite Yoga schools are largely Tantric in nature and include Kundalini Yoga, Hatha Yoga and Raja Yoga. Vaishnavism has many schools of Yoga, mainly of Bhakti Yoga, with Krishna himself as the avatar of Yoga, Yogavatara.

All Vedantic and Tantric traditions have their respective Yoga practices. Yoga is regarded as the means of perceiving the truth behind the teaching or philosophy, as Indic systems are ways of higher awareness, not simply conceptual frameworks. This allows Yoga to be adapted to various philosophical frameworks.

Yet all systems of Yoga begin with fundamental principles and practices of Dharma usually defined as yamas and niyamas, restraints and disciplines, which include the prime principles of dharma starting with non-violence and truthfulness, extending to an entire dharmic attitude and way of life.

Yoga and Buddhism

Yoga is a common term in Buddhist teachings, particularly in the Yogachara (Vijnanavada) line (a Mahayana school), one of the four main schools of classical Buddhist philosophy, and in Tantric Buddhism, specifically Vajrayana Buddhism (Buddhist Tantra commonly practiced in Tibet). Yet aspects of Yoga practice, particularly as mantra and meditation are common to all Buddhist schools, Theravada and Mahayana. Tibetan Anuttara Yoga has six limbs and appears as a kind of Raja Yoga like that of the Yoga Sutras.

Buddhism as a whole can perhaps be described as primarily a form of Jnana Yoga or the Yoga of knowledge owing to its emphasis on meditation. Yet Buddhism also has its Bhakti Yoga or devotional traditions as well which have been very popular throughout Asia, some good examples being the Lotus Sutra and also the worship of Amitabha as the Buddha of boundless light and the pure land. Buddhism has its rituals, extending to fire rituals to the Sun Buddha that resemble ancient Vedic fire rituals or Karma Yoga.

Like the Hindu schools, Buddhist schools of Yoga rest upon overall principles and practices of dharma as represented in the Four Noble Truths.

If we examine Hindu and Buddhist teachings overall, we see that different Hindu and Buddhist schools use similar Yoga practices, particularly pranayama, mantra and meditation, while differing in philosophy sometimes in considerable ways. In this regard, Yoga as a way of practice transcends any single philosophy, though it does rest upon a dharmic view of life. Some Yoga lineages, like that of the Siddhas, are honored in both Hindu and Buddhist traditions.

We must remember that all the schools of Hindu and Buddhist philosophy hold that the higher truth transcends all names, terms and concepts and dwells behind speech and mind. Yoga provides us the tools to directly experience that reality beyond all concepts.

Wherever Dharmic traditions have spread, which historically has been mainly to Southeast Asia, East Asia and Central Asia, some aspect of Yoga has gone with them, particularly practices of meditation.

Yoga has been the subject of modern scholarship as well, looking for connections between Yoga traditions. Some recent scholars have proposed a Yoga tradition as a greater tradition, of which such Indic traditions such as the Hindu, Buddhist and Jain are various manifestations. Others scholars look at Yoga as a kind of spiritual technology that can be useful for those pursuing higher consciousness from any angle or background, religion or philosophy East or West.

However, in traditional Hindu and Buddhist literature, we do not find a separate Yoga tradition that exists outside of Dharmic traditions, but rather we find Yoga as a manifestation of the Dharmic traditions.

Modern Yoga in the West

Yoga is a vast subject from ancient to modern times, and over the last two centuries has become a global phenomenon, with Yoga teachings spreading throughout the entire world. Yet the new modern Yoga, particularly in the West, has developed some characteristics of its own.

Most notably, reflecting the materialistic orientation of western civilization, modern Yoga has become more physical in nature, emphasizing asanas or Yoga postures as Yoga. Indeed for most people in the West, Yoga means asana and a Yoga class refers to an asana class. For the modern western mind a course in Yoga would likely be a course in styles of modern asana practice. This idea of Yoga as primarily asana has spread to some degree in India and the world as a whole. Asana can be a very good means to introduce people into Yoga, but only covers its outer dimension, not its inner essence and real import.

Sometimes this asana Yoga is referred to as Hatha Yoga, in order to differentiate it from Raja Yoga or deeper Yoga meditation practices. Yet even traditional Hatha Yoga contains extensive teachings on pranayama, mantra and meditation and is not centered on asana practice.

Yet the deeper aspects of Yoga have also spread globally with a greater interest in such internal practices as pranayama, mantra and meditation, through Kriya Yoga, Kundalini Yoga, and Advaita Vedanta, as well as the spread of devotional traditions of Bhakti Yoga. Modern Yoga-Vedanta movements in particular are of this type. Buddhism has mainly spread worldwide as a meditation tradition, but aspects of Buddhist Yoga have become widely practiced as well, particularly through Tibetan Yoga.

Ayurvedic Medicine

Not only is Yoga in various forms common to Hindu and Buddhist traditions, so are related teachings of Ayurvedic medicine. Ayurveda is the foundation of Indian medicine, including traditional Indian Buddhist medicine and Tibetan medicine. It remains widely practiced in Sri Lanka today. Ayurvedic medicine has spread globally along with Yoga and is now practiced in many Yoga centers throughout the world.

Ayurveda is rooted in the Vedas where it first appears as an Upaveda or secondary Vedic text. Vedic mantras and rituals are used for promoting health, well-being and longevity or ayu. Vedic texts mention the use of healing herbs and oils, purification and rejuvenation methods for both body and mind. They outline three primary powers of nature as Vayu or air, Agni or fire, and Soma as the watery principle, the basis of Vata, Pitta and Kapha, the three biological humors or doshas of Ayurveda.

Ayurveda can be regarded as the Yogic system of medicine and as the Dharmic system of medicine. It takes the principles of Dharma and the practices of Yoga and extends them into the realm of the healing arts for both body and mind, for both health maintenance and the treatment of disease. Ayurveda includes all forms of natural healing from diet to herbs and clinical methods. It has its sophisticated system of diagnosis and the determination of individual mind-body type or constitution.

Ayurveda takes the Yogic philosophy of prana and extends it to physical health and well-being through its concept of the three doshas or biological humors of Vata, Pitta and Kapha, which are the elements imbued with the power of Prana.

We find Ayurveda mentioned extensively in both Hindu and Buddhist Yoga texts, both for ordinary health issues of body and mind, and relative to the subtle energies created by Yoga practice. The medicine Buddha is an Ayurvedic figure who holds the seed of the Ayurvedic plant haritaki in his hand. The Buddha himself had an Ayurvedic doctor, Jivaka.

Traditional Ayurvedic texts like the Ashtanga Hridaya of Vagbhat of Sindh, the last of the three main Ayurvedic classics, mentions Buddhist deities like Avalokiteshvara. The three doshas and five pranas of Ayurveda occur in Buddhist Yoga as well, and are important in defining Pranayama practices.

The goal of all dharmic traditions is the alleviating of all suffering, which is by contrast the attainment of the supreme happiness and bliss.

Ayurveda shows us how to bring health and well-being to body and mind. Ayurveda can perhaps be described as the dharmic approach to health and well-being.

Classical Yoga shows us how to eliminate spiritual suffering, which comes only from the control of the mind.

Conclusion

It is important that Sanchi University look at not only the interface of Dharma and Dhamma in all forms, but also related teachings of Yoga and Ayurveda. Dharmic traditions address the whole of life and right living on all levels. They have several branches and a number of different names and applications.

Through such disciplines of Yoga and Ayurveda we can also find important points of communication and possible integration between Vedic and Buddhist traditions, and new areas of collaboration for the future. These extend to practical concerns of physical and psychological health and well-being, as well as social harmony.

Reclaiming Dharmic traditions and reclaiming Yoga traditions work together and support each other in a transformative manner.