Many people today look to Patanjali, the compiler of the Yoga Sutras, as the father or founder of the greater system of Yoga. While Patanjali’s work is very important and worthy of profound examination, a study of the ancient literature on Yoga reveals that the Yoga tradition is much older.

The traditional founder of Yoga Darshana or the ‘Yoga system of philosophy’ – which the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali represents – is usually said to be Hiranyagarbha. It is nowhere said to be Patanjali. The Mahabharata (Shanti Parva 349.65), the great ancient text in which the Bhagavad Gita of Sri Krishna occurs, states: “Kapila, the teacher of Samkhya, is said to be the supreme Rishi. Hiranyagarbha is the original knower of Yoga. There is no one else more ancient.”

Elsewhere in the Mahabharata (Shanti Parva 342.95-96), Krishna states, identifying himself with Hiranyagarbha: “As my form, carrying the knowledge, eternal and dwelling in the Sun, the teachers of Samkhya, who have discerned what is important, call me Kapila. As the brilliant Hiranyagarbha, who is lauded in the verses of the Vedas, ever worshipped by Yoga, so I am also remembered in the world.” Other Yoga texts like the Brihadyogi Yajnavalkya Smriti XII.5 similarly portray Hiranyagarbha as the original teacher of Yoga, just as Kapila is the original teacher of the Samkhya system. So do commentaries on the Yoga Sutras.

The vast literature of the Vedas, Mahabharata and Puranas speak of numerous great yogis but does not give importance to Patanjali, who was of a later period. Even the Yoga literature that is later in time than Patanjali, like that of Kashmir Shaivism or Hatha Yoga, does not make him central to their teachings. This is not to say that Patanjali is not honored, as his figure is found in many temples, particularly in South India but that the idea that Yoga begins with him at an historical level is not accurate. The Yoga Sutras remains an important text but its place in the tradition must also be recognized and its later date.

This earlier Yoga literature before Patanjali can be better called the Hiranyagarbha Yoga Darshana as it is said to begin with Hiranyagarbha. In fact, most of the Yoga taught in Vedas, Upanishads, Gita, Mahabharata and Puranas – which is the main ancient literature of Yoga – derives from it. Such ancient Pre-Patanjali texts speak of a Yoga Shastra or the ‘authoritative teachings on Yoga’ and of a Yoga Darshana or ‘Yoga philosophy’, but by that they mean the older tradition traced to Hiranyagarbha.

Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras is only referred to as a compiler, not as an inventor of the Yoga teachings. He himself states, “Thus is the teaching of Yoga” (Yoga Sutras I.1). This is quite unlike Krishna, the avatar of Yoga, who states, “I taught the original Yoga to Vivasvan” (Bhagavad Gita IV.1).

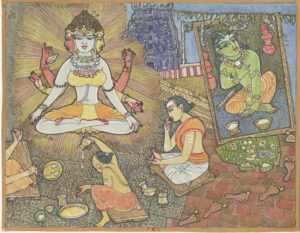

Patanjali is traditionally regarded as a devotee of Vishnu/Narayana, whose main human avatar is Krishna. This strongly suggests that Patanjali himself was a devotee of Krishna. Traditional Sanskrit chants to Patanjali laud him as an incarnation of Lord Sesha, the serpent on which Lord Vishnu/Narayana resides.

This Sesha attribution subordinates Patanjali and his darshana to Krishna/Vishnu. The depth, clarity and brevity of Patanjali’s compilation is noteworthy, but it is the mark of a later summation, not a new beginning.

The Bhagavad Gita is the primary ancient text lauded as a Yoga Shastra or ‘definitive Yoga teaching’. This can be carried to theMahabharata as a whole, in which the Gita occurs. Bhishma in the Mahabharata (Shanti Parva 300.57) also speaks of a Yoga teaching “established in many Yoga Shastras.” The Anu Gita section of the Mahabharata (Ashvamedha Parva 19.15) has an interesting section that begins, “Thus I will declare, the supreme and unequalled Yoga Shastra.”

Several Upanishads like the Katha are said to be Yoga Shastras, besides numerous Yoga Upanishads that also do not emphasize Patanjali. The Puranas contain sections on Yoga said to be authoritative in nature as well and do not give importance to Patanjali. When such texts teach Yoga, they often do so with quotes from the older Vedas.

This means that the Patanjali Yoga Darshana is a later subset of the earlier Hiranyagarbha Yoga Darshana. It is not a new or original teaching, nor was it ever meant to stand on its own. The topics addressed in it from yamas and niyamas to dhyana and samadhi are already taught in detail in the older literature. In the Mahabharata (Shanti Parva 316.7), the sage Yajnavalkya speaks of an “eightfold Yoga taught in the Vedas.” The Shandilya Upanishad (1) refers to an eightfold or ashtanga Yoga but does not mention Patanjali.

While no single simple Hiranyagarbha Yoga Sutras text has survived, quite a few of its teachings have remained. In fact, the literature on the Hiranyagarbha Yoga tradition is much larger than that on Patanjali Yoga tradition, which itself represents a branch of it. We cannot speak of a Patanjali Yoga tradition or of a Patanjali Yoga literature apart from this older set of Yoga teachings rooted in the Hiranyagarbha tradition. The Patanjali Yoga teaching occurs in the context of a broader Yoga Darshana that includes other streams. There is only one Yoga Darshana that existed long before Patanjali and was taught in many ways. It is the Yoga Darshana attributed to Hiranyagarbha and related Vedic teachers.

Hiranyagarbha and Vedic Yoga

Who then was Hiranyagarbha, a human figure or a deity? The name Hiranyagarbha, which means “the gold embryo”, first occurs prominently as a Vedic deity, generally a form of the Sun God. There is a special Sukta or hymn to Hiranyagarbha in the Rig VedaX.121, which is commonly chanted by Hindus today. The Mahabharata speaks of Hiranyagarbha as he who is lauded in the Vedic verses and taught in the Yoga Shastra (Shanti Parva 339.69). As a form of the Sun God, Hiranyagarbha can be related to other such Sun Gods like Savitri, to whom the famous Gayatri mantra is addressed. Therefore, the Hiranyagabha Yoga tradition is a strongly Vedic tradition. We can call it the Hiranyagarbha Vedic Yoga tradition.

Krishna states in the Bhagavad Gita (IV.1-3) that he taught the original Yoga to Visvasvan, another name of the Sun God, suggesting Hiranyagarbha. Vivasvan taught this Yoga to Manu, the original man or first king, making it into the prime Yoga path for all humanity.

The Mahabharata (Shanti Parva 340.50) additionally identifies Hiranyagarbha, as other texts do, with Brahma or Prajapati, the creator among the Hindu trinity, who among other things represents the Vedas and is the source of all higher knowledge. It also identifies Hiranyagarbha with the Buddhi or Mahat, the higher or cosmic mind (Mahabharata 302.18), with which Brahma is often connected.

The chief disciple of Hiranyagarbha in the ancient texts is said to be the Rishi Vasishta, the foremost of the Vedic seers (seer of the seventh book of the Rig Veda), who passed on the Yoga teachings to Narada (Mahabharata Shanti Parva 308.45). Vasishta teaches the Yoga Darshana in the Mahabharata (Shanti Parva 306.26): “The Yoga Darshana has so been declared by me according to the truth.” He also passes on his knowledge to his son, Parashara, in whose line was born Veda Vyasa, who compiled the Vedas and wrote the Mahabharata.

Vasishta is made into the prime early human teacher of such other Vedic disciplines as Advaita Vedanta (the tradition of Jnana Yoga or the Yoga of Knowledge), and of carrying on the Yoga teachings of Shiva and Vishnu as well as that of Hiranyagarbha. There are several very important Yoga texts in the Vasistha line including the Vasishta Samhita and Yoga Vasishta, the latter of which is often regarded as the greatest work on both Yoga and Vedanta.

The original Yoga tradition is not the Patanjali tradition but the Hiranyagarbha tradition. It teachings are found not only in the Yoga Sutras but in the Mahabharata, including the Bhagavad Gita, Moksha Dharma Parva and Anu Gita, which each contain extensive teachings on Yoga from many sides. The Hiranyagarbha Yoga tradition is the main Vedic Yoga tradition. The Patanjali Yoga tradition is an offshoot of it or a later expression of it.

Samkhya, Yoga and Vedanta are all presented as aspects of this same tradition in the Mahabharata. Ayurveda and Vedic astrology are important aspects of its outer application. If we want to go back to the real roots of Yoga and restore the original teachings of Yoga, we should return to the Hiranyagarbha Yoga Darshana. It will also help us better understand the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali.

Distortions of the Yoga Sutras

Much of modern Yoga rests upon a misinterpretation and misunderstanding of the Yoga Sutras. The first problem is that many people try to look at the Yoga Sutras as an original text that stands in itself, when it is only a later compilation that requires examining its background in order to make sense of it. This causes them to separate Yoga from the earlier Vedic tradition that forms the greater context of Patanjali’s teachings.

Second, the Yoga Sutras, as a sutra work consisting of short aphorisms, can be easily slanted in different directions according to the inclinations of the interpreter. The teachings of the Hiranyagarbha Yoga Darshana, on the other hand, are more complete and can be cross referenced to avoid such distortions.

Third, the Yoga Sutra tradition has been made sectarian, notably opposing Yoga and Samkhya to Vedanta. This is not something of the modern age only, but occurred in old debates between these philosophical systems going back to the Middle Ages and before. The original Hiranyagarbha Yoga Shastra, however, is presented as in harmony with Samkhya and Vedanta, such as we find it in the Mahabharata. The synthesis of these three systems is in fact as old as Krishna, if not older.

This older integral Yoga is the same general type of Yoga-Vedanta taught by great modern Yoga gurus of India like Vivekananda, Yogananda, Aurobindo, Shivananda, and his many disciples, and many others, the very teachers who first brought Yoga to the West in the last century. They have taught the Yoga Sutras, the Bhagavad Gita and the Upanishads together as part of the same broader tradition.

So how do we approach the Yoga Sutras then? It is best to do so in the context of the older Yoga Darshana. There is only one Yoga Darshana through all the texts and tradition. There is no Patanjali Yoga Darshana as an entity in itself apart from the older Hiranyagarbha Yoga Darshana. If we want to understand the meaning of the technical terms in the Yoga Sutras, we should do so with recourse to the older literature, not by inventing our own meanings or trying to make these terms unique to the Yoga Sutras. Whether it is the yamas and niyamas, the different types of samadhi, or the different aspects of Yoga practice, all such terms often alluded to only briefly in the Sutras can be found explained clearly and in detail in the older literature.

In addition, we should look at the Yoga Sutras in light of Vedanta, not only the Bhagavad Gita but also the Upanishads. While Patanjali emphasizes the Purusha rather than Brahman (the Absolute), we must remember that the Hiranyagarbha tradition gives Brahman its place. We can also look to Vedanta for a greater description of Ishvara or God, which Patanjali does not examine in detail, but which Vedantic texts examine in great detail.

This means that we should delink Yoga per se from Patanjali and restore its meaning at a broader level. We should look at Yoga beyond the Yoga Sutras, not only the ancient Yoga literature before Patanjali but the later Yoga literature apart from him, the various traditions of Vaishnava, Shaivite, Shakta and Vedantic Yoga. Once we do this we can understand why different aspects of Yoga have been used by different philosophical systems in India, including those who may not agree with Patanjali on certain philosophical issues. Yoga as a general tradition is something more than Patanjali, however great his compilation may be. Most of that broader Yoga can be found in the earlier Hiranyagarbha formulation, particularly in the Mahabharata.

Besides looking at Patanjali in a new light, we should work to restore the teachings of the Hiranyagarbha Yoga Darshana. Many of these can easily be compiled from the Mahabharata, Upanishads, and other ancient Vedic teachings. Through it we can gradually reclaim the older Vedic Yoga it was based upon. In this way, we can restore the spiritual heritage of the Himalayan rishis. This is an important task for the next generation of Yoga aspirants, if they want to really reclaim the origin and depths of the teaching.

David Frawley