- From darkness lead us to light, from non-being lead us to being, from death lead us to immortality. Brihadaranyaka Upanishad I.3.28

- I laud the flame of awareness that is placed before all things, the deity of the sacred ritual, who manifests by the seasons, the invoker of the Gods, best to grant the treasure.

- The flame is the invoker, the seer-will, the manifold knowledge of truth, Divine may he come with all the Divine powers.

Rig Veda I.1.1, 5

- Not what one knows with the mind, but that by which the seers declare the mind is known. This is the reality that you should know, not what people regard as an object in this world. Kena Upanishad I.5

Introduction to Vedanta

The first teachers who brought Yoga to the West came with the profound teachings of Vedanta as their greatest treasure to share with the world. Vedanta is the philosophy of Self-realization, the unity of Self and the Divine that Yoga as unity indicates. Such great masters began with Swami Vivekananda at the end of the nineteenth century and continued with Swami Rama Tirtha, Paramahansa Yogananda, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the many disciples of Swami Shivananda of Rishikesh and more, including Ramana Maharshi whose teachings went worlwide without him ever leaving India. They called their teaching Yoga-Vedanta, which they viewed as a complete science of consciousness as individual and cosmic levels.

However, in the course of time asana gained more popularity in the physically-minded West, and the Vedantic aspect of the teachings receded into the background. The result is that few Yoga teachers know what Vedanta is or can explain it to others. If they have an interest in meditation they often look to Buddhist meditation, not knowing that meditation is the very foundation of classical Yoga.

Students of Ayurveda or Vedic astrology may know little about Vedanta, the path of self-knowledge that is the spiritual support and goal of these Vedic systems. Those who study the great Vedantic gurus of modern India,like Ramana Maharshi or Nisargadatta Maharaj, generally look at the particular teacher as the source of the teachings, and may fail to understand the ancient tradition they are part of. The core teachings of India’s great sages can become forgotten to those who follow their teachings.

The great sages of modern India were Vedantins. Most notable is Ramana Maharshi, who emphasized the non-dualistic form of Vedanta and lived a life of direct Self-realization. Ramakrishna, Aurobindo, Anandamayi Ma, Nityananda, and Neem Karoli Baba, to mention but a few, were also Vedantins, using the Vedantic terminology of Self-realization and God-realization. Vedantic traditions remain strong in India today, including many great tradition teachers, for example, the Shankaracharyas, who have never come to the West.

Mata Amritanandamayi (Ammachi) and also Satya Sai Baba used the language of Vedanta and its emphasis on the Self. Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s Transcendental Meditation follows a Vedantic view of consciousness and cosmic evolution. Swami Rama, the founder of the Himalayan Institute, was another important Vedantic teacher in America. The main Hatha Yoga teachers in recent times, like Krishnamacharya follow Sri Vaishnava Vedantic teachings for the higher aspects of Yoga. Devotional approaches like the Hari Krishna movement follow Vedantic devotional teachings (Bhakti-Vedanta).

The Philosophy of Vedanta

Vedanta is a simple but profound philosophy. It states that our true Self, what it calls the Atman, is God or the Divine. “I am God” (aham brahmasmi) is the supreme truth. The same consciousness that resides at the core of our being pervades the entire universe. To know ourselves is to know the Divine and to become one with all. Vedanta is the philosophy of Self-realization, and its practice is the way of Self-realization through yoga and meditation.

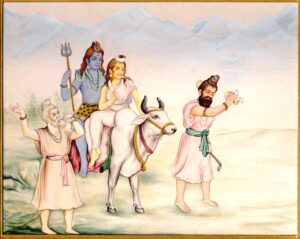

Vedanta has a theistic side, recognizing a cosmic creator (Ishvara) who rules over the universe. Ishvara is the supreme teacher, the highest guru from whom all true teachings arise by the power of the Divine Word OM. Vedantic theism takes many forms such as the worship of Shiva, Vishnu, the Goddess in her numerous forms, Rama, Krishna and Ganesha.

In non-dualistic (Advaita) Vedanta, the Creator is not the supreme reality. The ultimate reality is the Absolute, Brahman, which transcends time, space and causation, any personal creator or embodied soul. Our individual Self or soul (Atman) is one with the Absolute or Brahman, which is the supreme Self (Paramatman). The reincarnating soul is not merely a part of the Creator but is one with Brahman of Being-Consciousness-Bliss from which even the Creator arises.

Vedanta is the oldest and most enduring spiritual teaching in India rooted in the Vedas. It is explained in the Upanishads and synthesized in the Bhagavad Gita. It has ancient antecedents in Vedic literature, which recent archaeological finds now date to before 3500 BCE when the ancient Rishi-based Indus-Saraswati culture flourished throughout India. The main terms and practices of Vedanta exist in the cryptic mantras of the ancient Vedas that go back to the dawn of history, as a cosmic not merely an Earth-based teaching.

Spirituality should be a pursuit of self-knowledge, not merely belief or dogma. Vedanta is the most characteristic philosophy of India and Yoga. Vedanta literally means “the end of the Vedas” but more appropriately it refers to the essence of the Vedas. From the standpoint of great yogis like Sri Aurobindo, the Vedas present the truth of Vedanta in a poetic-mantric language, while Vedanta presents Vedic mantric knowledge in the form of a rational philosophy. The wisdom hidden in the mantras of the ancient Rishis shines forth in the clear insight approaches of Vedanta.

Vedanta and Buddhism

Vedanta in the Upanishads preceded Buddhism by some centuries. Vedanta and Buddhism have much in common as ways of spiritual knowledge born of the Indic dharmic tradition. Many scholars see Buddhism as a modification of Vedanta. Vedantic teachers accepted Buddha as an incarnation (avatara) of Lord Vishnu, like Rama and Krishna.

Vedanta and Buddhism share ideas of karma, rebirth, and release from the cycle of rebirth (samsara). They have similar practices of mantra and meditation. They follow the same ethical disciplines of non-violence (ahimsa) and vegetarianism, and both have well-developed monastic orders. The Mahayana form of Buddhism and Advaita (non-dualistic) Vedanta have a similar emphasis on the Absolute and regard the phenomenal world as maya or illusion, an outer appearance not the inner reality.

Like Zen Buddhism, non-dualistic Vedanta emphasizes the Self or Self-nature as the supreme Reality. It honors that Self in the world of nature. Vedantic gurus laud the great beauty of nature, revealed through mountains such as the Himalaya, as reflections of our true being beyond the world of impermanence.

Buddhist meditation aims to return to the natural state of the mind as the enlightened state. This occurs through negating the self or ego and awakening the Buddha-mind (Bodhichitta). Vedanta is based on a clear distinction between the mind (manas), which is regarded as a product of ignorance or maya, and the Self (Atman), which transcends the mind. The Vedantic way is to dissolve the mind into the Self which is our true nature beyond the mind and its karmas.

While Vedanta approaches pure awareness as the Self or Atman, Buddhism prefers the term anatman or non-self. We also find such utterances of the Divine I am in pagan traditions, like those of the Celtic Druids, Greeks and Egyptians, which have many factors in common with Hinduism.

Vedantic Meditation

Dhyana, the Sanskrit term for meditation used by Hindus and Buddhists alike, first arises in Vedic literature. The Upanishads say, “By the Yoga of meditation (Dhyana Yoga) the sages saw the Divine Self-power, hidden in its own qualities” (Shvetasvatara UpanishadI.2). Another Upanishad states, “Meditate on Om as the Self” (Katha Upanishad II.5), showing the technique of mantra meditation.

Perhaps the most eloquent explication of meditation occurs in the Chhandogya, one of the oldest Upanishads. “Meditation (Dhyana) indeed is greater than the mind. The earth as it were meditates. The atmosphere as it were meditates. Heaven as it were meditates. The waters as it were meditate. The mountains as it were meditate. Both men and gods as it were meditate. He who worships God (Brahman) as meditation, as far as meditation extends, so far does he gain the power to act as he wills” (Chhandogya Upanishad VII.7).

According to Vedanta, liberation can be achieved only by Self-knowledge, which requires meditation. Other factors, such as good works or rituals, are aids in the process. But such liberating knowledge is not any ordinary or conceptual knowledge. It is direct insight into one’s own nature as pure consciousness.

Vedanta’s main approach is threefold: 1. hearing the teaching with a receptive mind (shravana), 2.deep thinking about it (manana), and 3. meditating on it consistently (nididhyasana) until full realization dawns, which is a state of samadhi or transcendent awareness. Such hearing is not simply noting the words of the teachings; it involves a deep inner listening with an open mind and heart. Such thinking requires full concentration and a firm intent to understand oneself. Such meditation is a repeated practice of self-examination and self-remembrance throughout the day as one’s primary mental state.

Vedanta is a yoga of knowledge or a path of meditation. But it recognizes that other yogic paths are helpful, if not indispensable adjuncts, particularly the path of devotion (Bhakti Yoga), which takes to the Divine presence in the heart. Vedanta employs all the limbs of classical yoga from asana to samadhi, using all methods of the yogas of knowledge, devotion, service and technique, depending upon the needs of the student.

Vedanta does not prescribe any single form of meditation en masse or give the same technique to everyone. Emphasizing the Self, it recommends different approaches relative to the level and temperament of each person and his or her unique nature and life circumstances. Self-inquiry is applied on an individual basis, in which its methods can vary greatly from one person to another.

Vedantic meditation is generally private, emphasizing individual practice. However, meditation sessions do occur as part of the satsangs or gatherings that are common in the tradition. These may extend over a period of days or weeks. Yet those participating in such sessions may practice different forms of meditation, based upon the specific instructions of their teachers.

With its theistic side Vedanta recognizes surrender to the Divine as a spiritual practice along with Self-inquiry. Yet surrender, though easy to conceive, is a difficult process because it requires giving up the ego and the fears and desires that go with it. This way of surrender is aided by chanting of Divine names and other devotional forms of worship. These can be practiced along with knowledge-oriented techniques like Self-inquiry.

In the Vedanta we approach the Creator as a means of discovering our true Self. Union with the Divine is part of the process of Self-realization. The Deity worshipped is ultimately the same as oneself and we must see it in all beings. Until we see the Divine beloved within our own heart, our devotion has not yet reached its highest goal.

Vedanta recognizes the supreme reality as Being, Consciousness, and Bliss (called Satchidananda), which is eternal and infinite. Vedanta follows an idealistic philosophy much like the Greek philosophies of Plato, Plotinus or Parmenides. Part of Vedantic meditation is contemplating these higher principles–meditating on the formless Absolute and its laws (dharmas) behind the world of nature.

Meditation on the oneness of all is another important Vedantic approach. Vedanta sees pure unity as the supreme principle in existence. It recognizes a single law or dharma governing the entire universe. Whatever we do to others we do to ourselves because there is only one Self in all. This is the basis of Vedantic ethics that emphasize non-violence and compassion, treating others as our own Self.

Note our book Vedantic Meditation

Return to Oneness

Vedantic meditation aims at returning us to this original state of unity, in which all beings abide in the Self within the heart.

Like most Indian spiritual systems, its purpose is to show us how to permanently remove all suffering. Vedantic meditation involves meditating upon suffering and removing its cause. Vedanta regards ignorance of our true Self as the cause of all our life problems.

Because we don’t know our true Self, which is pure awareness beyond body and mind, we must suffer, seeking happiness in the shifting external world but never finding it. By returning to our true Self we can transcend psychological suffering and detach ourselves from physical suffering. The pain of body and mind do not belong to the Self that is beyond time and space.

Vedanta has a profound understanding of the different layers and functions of the mind, from the unconscious to the highest superconsciousness, for which it has a precise terminology. Vedanta regards the ego (ahamkara) or the false I, the I identified with the body, as the basis of all sorrow.

Vedanta recommends regular meditation for everyone, particularly during the hour or two before dawn, which it calls Brahma Muhurta or the hour of Brahman. Sunrise and sunset are other important times for meditation because at these transitional periods in nature, energy can be more easily transformed. The times of the new, full and half moons are also excellent, as are solstice and equinox points. Meditation is part of the very rhythm of life and nature and its ongoing transformations.

Very important for meditation is the period immediately before sleep in order to clear the day’s karma from the mind. Vedanta regards the deep sleep state as the doorway to the Self, our natural daily return to God. Its practices develop our awareness through waking and dream to deep sleep and beyond. Deep sleep is the knot of ignorance; when it is removed vy meditation, we can discover our true nature and eternal peace. Maintaining awareness through dream and deep sleep is an important Vedantic approach.

Vedanta is perhaps the world’s oldest continuous meditation tradition. Like our eternal reincarnating soul, it witnesses all the changes of time and history. It takes on new forms and inspires new teachers in every generation. Such an ancient and diverse meditation tradition is of great importance for all those who wish to understand what meditation really is and how best to practice it, particularly those in Yogic and Vedic traditions.

OM Sri Veda Purushaya Namah!

Vamadeva Shastri